El Errante

(All material in this dispatch was approved for release by the relevant parties)

“We were in an Assembly at the Polytechnic discussing solidarity with political prisoners, and many were interested in helping with money and support. No one had any money so we squatted Vox and made it into a café to make money.”

I am sitting in the Vox cafe with Tharasis, an anarchist associated with the space and the action group Rubicon. The space is huge by my standards, airy—massive windows open out onto Exarcheai Square, multiple tables and chairs, a small bar with an espresso machine, and a fridge stuffed with beer stands to one side. A small library is also present. Tharasis continues, “So far we have made 160,000 euro to help the prisoners.”

“That’s a lot…” I mutter.

“Not really, we pay no rent, no electricity, nothing. It helps, though, prisoners in Greece get nothing. They have to buy everything, toilet paper, toothpaste, everything,” he says as he lights another cigarette.

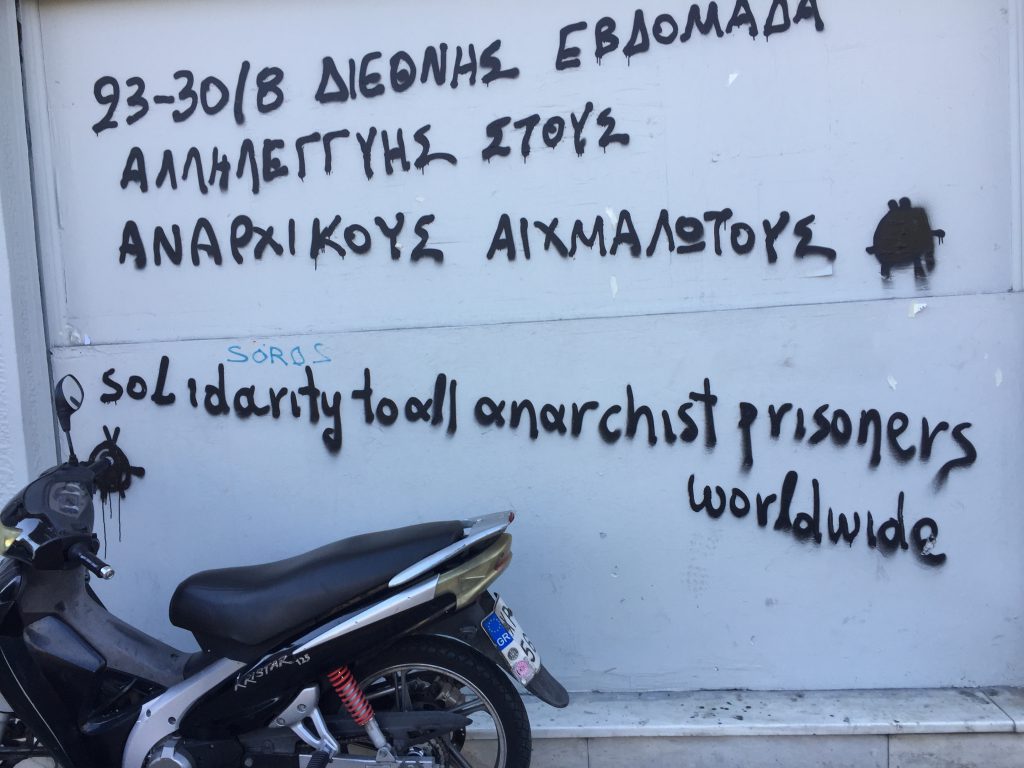

“Who do you help, what kinds of prisoners?”

“Mostly anarchists, nihilists, some others, we make sure that the activities they were imprisoned for were political, and that in prison they have shown solidarity. That’s it. We don’t have a test to see if they meet our standards.”

Vox also houses a small medical and dental clinic in the basement, an initiative that came from outside the Vox collective but was considered important enough to support. The space also hosts other assemblies and groups.

“And then Rubicon…” I ask.

“Well Rubicon is different, out of the people who squatted Vox and whose primary concern was solidarity with political prisoners, a new concern arose. Many of us saw the movement begin to lose motion, to freeze.”

“Like how? What gave you that impression?”

“Fewer people at demos and assemblies, less interest.”

“Okay so you formed Rubicon….”

“Yes, Rubicon. A smaller group for direct action. We formed it to keep the light on, to show the state and our comrades that anarchy still lives.”

“And the targets of your actions….”

“All planned, we look for targets that will affect people, that are socially relevant. Like Le Pen’s party renting a space in Athens, or the agency responsible for privatization. And we let people know who we are, what we want, and how to contact us.” It should also be noted that Rubicon, in an action at the Greek parliament protesting prison conditions, found themselves in the uncomfortable position of finding a door into the building open and unguarded. A quick consensus was reached that maybe it wasn’t the best day to seize and destroy the state.

“All planned, we look for targets that will affect people, that are socially relevant. Like Le Pen’s party renting a space in Athens, or the agency responsible for privatization. And we let people know who we are, what we want, and how to contact us.” It should also be noted that Rubicon, in an action at the Greek parliament protesting prison conditions, found themselves in the uncomfortable position of finding a door into the building open and unguarded. A quick consensus was reached that maybe it wasn’t the best day to seize and destroy the state.

We also watched the video of the Le Pen offices being ransacked and he commented, laughing, “Did you see? The comrade with the hammer is using the wrong side of the head! It’s terrible.”

“What about security?”

“The people who participate are masked, and without identity the state can do little. I was arrested but the charges were dropped—the video shows masked people—not us.”

“And how many people usually participate?”

“That all depends on the action. Some require only one or two. Others, dozens. When we attacked the state agency for privatization it took many people. It’s a big building and we needed time to destroy all the office computers. Others, like the parliament action, maybe 10 or 15.”

“And,” I ask, “what of now…?”

“What’s happening now is critical, what we do as Rubicon seeks to reignite the anarchist movement.”