El Errante

Democracy—”a system of government in which all the people of a state or polity … are involved in making decisions about its affairs, typically by voting to elect representatives to a parliament or similar assembly,” (a:) “government by the people; especially: rule of the majority” (b:) “a government in which the supreme power is vested in the people and exercised by them directly or indirectly through a system of representation usually involving periodically held free elections.”—Oxford English Dictionary

I hate democracy. And I hate organizations, especially communes. Yet, I favor the organization of democratic communes.

THIS: Democracy is always about mediation. Whether it separates the subject from decision-making, functions as an excuse for graft and fraud, or whether it separates the subject from him or herself. Democracy stands in the way of the individual, blocks unmediated communication by imposing the requirement of structure—an outcome, a decision. And when a decision is reached, it is usually arrived at by the most banal and ruthless method ever devised: the vote—the tyranny of the majority.

Anarchism has had a mixed history of criticism regarding democracy. Étienne de La Boétie in his Discours lays out a first line of inquiry by wondering why it is that people allow themselves to be governed at all—and as he explores the problem he points out that it seems not to matter whether a tyrant is chosen by force of arms, by inheritance, or by the vote. He states,

“For although the means of coming into power differ, still the method of ruling is practically the same; those who are elected act as if they were breaking in bullocks; those who are conquerors make the people their prey; those who are heirs plan to treat them as if they were their natural slaves.” (1)

And it might be added that the subject population submits to such abuse without question or contestation. La Boétie’s treatise is truly prescient; written in (roughly) 1553—a full 250 years before the emergence of the modern nation-state—and yet it contemplates exactly the type of unbridled war, oppression, and terror that democratically elected governments were to unleash on subject populations, and each other.

Power cannot exist in a vacuum, as the monarchs of Europe learned during the upheavals of 1848 while they watched their respective regimes disintegrate, one after the other. With democracy came the calculation of exchange, one iota of power given to a citizen via the vote, produces a vast quantity of power ensconced in legislature, executive, and judiciary. It’s unsurprising that political systems began to apply equations of power and exchange at the same time that in the economic realm Capital was introducing similar equations in order to usurp labor-time in trade for survival. Further such an exchange ties the population all that much closer to the rulers. Vanegeim illustrates the mechanism thus,

“Slaves are not willing slaves for long if they are not compensated for their submission by a shred of power: all subjection entails the right to a measure of power, and there is no such thing as power that does not embody a degree of submission.” (2)

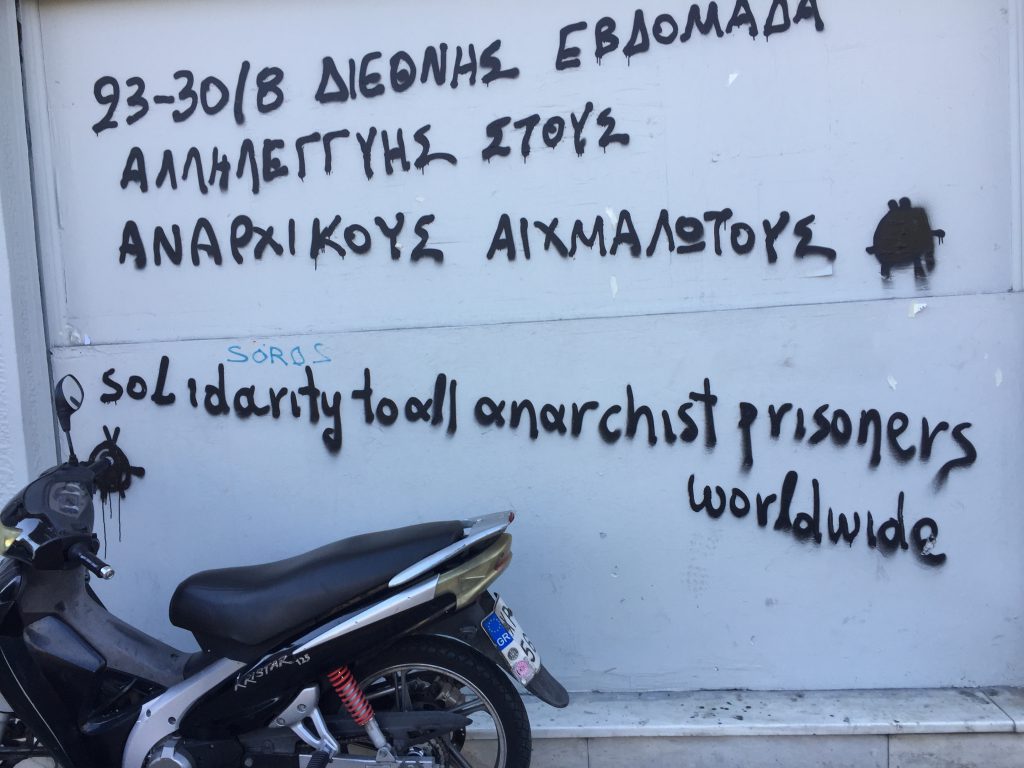

It is Proudhon who will have the most varied interaction with  democracy, both theoretically and practically. His career includes writing and publishing tomes of critical analysis denouncing democracy, running for elected office, serving in the National Assembly during the 1848 Revolution, and finally returning to his original rejection of voting and representation. He will also urge his followers to alternately abstain from voting, then to vote, then to abstain from voting (again), and finally to cast blank ballots to protest voting.

democracy, both theoretically and practically. His career includes writing and publishing tomes of critical analysis denouncing democracy, running for elected office, serving in the National Assembly during the 1848 Revolution, and finally returning to his original rejection of voting and representation. He will also urge his followers to alternately abstain from voting, then to vote, then to abstain from voting (again), and finally to cast blank ballots to protest voting.

Proudhon unleashed a number of critiques on democracy. The critical prisms he used vary greatly, from the purely psychological to the empirical. And the targets of his barbs span the entire menagerie of democratic platitudes from the myth of “The People” to sovereignty to the realpolitik of how legislatures operate. Of interest is his critical analysis of the democratic decision-making process itself. He scrutinizes the mechanism of the vote and its outcome; specifically majority rule. He reasons in this manner,

“Democracy is nothing but the tyranny of majorities, the most execrable tyranny of all, for it is not based on the authority of a religion, nor on a nobility of blood, nor on the prerogatives of fortune: it has number as its base, and for a mask the name of the People…”

But Proudhon doesn’t finish there; he goes on to protest that those left in the minority are forced by circumstance to follow the will of the majority. A situation he finds untenable, not only for the explicit coercion but also because those in the minority are forced to abjure their ideas and beliefs in favor of those who oppose them. This, he notes wryly, makes sense only when political views are so loosely held  by individuals as to hardly be worthy of the name. William Godwin, in analyzing the same scenario provides the terminal statement, “nothing can more directly contribute to the deprivation of the human understanding and character” than to require people to act contrary to their own reason. A conclusion proven empirically when one conducts even the most rudimentary survey of representative government and its effects on humanity over the course of the past 250 years.

by individuals as to hardly be worthy of the name. William Godwin, in analyzing the same scenario provides the terminal statement, “nothing can more directly contribute to the deprivation of the human understanding and character” than to require people to act contrary to their own reason. A conclusion proven empirically when one conducts even the most rudimentary survey of representative government and its effects on humanity over the course of the past 250 years.

In conclusion—for an anarchist, for myself, democracy—as a system of self-governance, as a decision-making tool, as an ideal—is utterly devoid of any redeeming value or usefulness. It functions as a mask for coercion, making horror palatable whilst producing unbearable consequences for the individual, for the species, and for the planet. A dead end.

THAT: It is at this point that most anarchists and critical theorists begin backpedaling, some slowly (like Proudhon) and others rapidly (like Bookchin). Historically theorists have offered a scathing critique of democracy and then have immediately digressed, stating that the representative form of democracy as conceived by bourgeois (or socialist) society isn’t really democracy. That real democracy is reflected in some other form—for Proudhon delegated democracy, for Bookchin the Greek city-states, or the Helvetican Confederation. The argument then becomes that democracy can (and should) be recuperated by the Left as a workable form.

My own critique veers wildly off course at this point by virtue of having been skewed by empirical observation of a different form of democratic practice. Having recently returned from the Kurdish Autonomous Region in Northern Syria, known as Rojava, I had the opportunity to observe a unique form of unmediated democracy as implemented by a revolutionary libertarian social movement.

Some theoretical context: Abdullah Öcalan, the head of the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (PKK, The Kurdistan Worker’s Party) was captured by Turkish Security Forces, with assistance from the CIA and Israel’s Mossad, in 1999. Dodging a firing squad, he was eventually sentenced to aggravated life imprisonment and that’s when things get interesting. Eschewing making license plates, or working in the laundry, Öcalan began the long slow intellectual journey out of Marxist-Leninist jibberish and into some pretty durable anarchist theory. Eventually publishing his ideas in several works, including Democratic Confederalism, War and Peace in Kurdistan, and a multi-volume tome on civilization, particularly the Middle East and Abrahamic religions. In his writing Öcalan does what no one else in the contemporary North American anarchist milieu is even willing to think—he constructs, albeit vaguely—a blueprint for a libertarian society. This simple exercise, devoid of content, is incredible. His engagement resembles far more the utopian socialist project of the early 19th Century than any of the ensuing theoretics associated with social contestation—especially Marxism and working-class anarchism; indeed his silence on class analysis, Marxist teleology, historical materialism, and syndicalism is deafening. Öcalan is clear in his task when he states in the Principles of Democratic Confederalism, “Democratic confederalism is a non-state social paradigm. It is not controlled by a state. At the same time, democratic confederalism is the cultural organizational blueprint of a democratic nation.[bold mine]”

As implied in the name, there is a great reliance on democratic processes in the system known as Democratic Confederalism. Yet here Öcalan is silent in his definition of democracy—he never offers one—and in it’s implementation—he never discusses it with any specificity. In fact, democracy is presented as a given, as a decision-making process, as an approach to self-administration, and little else. There is no favoring of voting versus consensus-based models, nor does he describe in any detail, at any level (communal, cantonal, regional) the forms that he foresees democracy taking. As an example,

“[Democratic Confederalism]…can be called a non-state political administration or a democracy without a state. Democratic decision-making processes must not be confused with the processes known from public administration. States only administrate [sic] while democracies govern. States are founded on power; democracies are based on collective consensus.” (4)

He then expands on what he means by “decision-making processes” in  the Principles of Democratic Confederalism, “Democratic Confederalism is based on grass-roots participation. Its decision-making processes lie with the communities.” Fair enough. So how does all this play out in Rojava? In other words, how are Öcalan’s ideas being translated into revolutionary institutions?

the Principles of Democratic Confederalism, “Democratic Confederalism is based on grass-roots participation. Its decision-making processes lie with the communities.” Fair enough. So how does all this play out in Rojava? In other words, how are Öcalan’s ideas being translated into revolutionary institutions?

My first insight into democracy in Rojava happened over a plate of hummus and pita in downtown Kobanî. I was sitting with Mr. Shaiko, a TEV-DEM (Tevgera Civaka Demokratîk, Movement for a Democratic Society) representative on a warm, dusty afternoon, some three days after attending a commune meeting together. In that meeting, of the council of Şehid Kawa C commune, Mr. Shaiko had raised the issue of commune boundaries and perhaps moving them in allowance for the number of people returning to the rubbled, venerable hulk that is Kobanî. After some discussion and as Mr. Shaiko left the meeting, he requested a phone call to let him know what was decided.

So I asked Mr. Shaiko, “What happened with the commune? Did they call?”

“No, no decision yet.”

“Oh, do they need to give one?”

“No, they’ll decide when they’re ready. That’s how it is,” Mr. Shaiko looked at me over his glasses with a half-grin and then returned to the plate of pita and hummus.

Clearly a divergent view of democratic decision-making where no conclusive result is as valid a response as a “yes” or a “no.” While I only saw this adjustment to democratic decision-making in operation a few times it seems to be fairly common, especially with the TEV-DEM folks whose charge is implementing democratic confederalism. It is also an interesting “fix” applied to the issue of decision-making processes. In one sense it negates the democratic process in favor of discourse, argument, and engagement without the concomitant requirement of an outcome.

Clearly a divergent view of democratic decision-making where no conclusive result is as valid a response as a “yes” or a “no.” While I only saw this adjustment to democratic decision-making in operation a few times it seems to be fairly common, especially with the TEV-DEM folks whose charge is implementing democratic confederalism. It is also an interesting “fix” applied to the issue of decision-making processes. In one sense it negates the democratic process in favor of discourse, argument, and engagement without the concomitant requirement of an outcome.

The response of the revolutionaries to the tyranny of majority rule has been structural rather than directive. Here Öcalan describes his views on a plural society and in so doing outlines how he plans to weaken or subsume majority rule,

“In contrast to a centralist and bureaucratic understanding of administration and exercise of power confederalism poses a type of political self-administration where all groups of the society and all cultural identities can express themselves in local meetings, general conventions and councils…We do not need big theories here, what we need is the will to lend expression to… social needs by strengthening the autonomy of the social actors structurally and by creating the conditions for the organization of the society as a whole. The creation of an operational level where all kinds of social and political groups, religious communities, or intellectual tendencies can express themselves directly in all local decision-making processes can also be called participative democracy.”

So for the revolutionaries the formation, growth and proliferation of all types of “social actors”—communes, councils, consultative bodies, organizations and even militias is to be welcomed, and encouraged—strongly.

This plays out in Rojava in an insane patchwork quilt of organizations, interests, local collectives, religious affiliates, and…flags. TEV-DEM, the umbrella organization charged with implementing democratic self-administration, is actually an agglomeration of several smaller organizations and representatives from political parties. These various subaltern organizations include those whose priority is sport, culture, religion, women’s issues, etc… As an example of this proliferation, in December of 2015 a new organization under the TEV-DEM system was born—TEV-ÇAND Jihn, whose priority is women and cultural production. This new organization is in addition to the generic TEV-ÇAND, whose priority is society, generally, and cultural production. In order to derail issues of majority rule the revolutionaries have introduced a structural caveat that allows individuals to find a majority that suits their needs, and through which their voice can be heard in society. Note that  TEV-DEM and others have not sought to tinker with the actual mechanics of how a commune or organization operates or decides. Rather, they have changed the social order such that if an individual refuses to uphold a decision by a group, commune or council, the ability to opt out and find a more amenable assembly of folks is available.

TEV-DEM and others have not sought to tinker with the actual mechanics of how a commune or organization operates or decides. Rather, they have changed the social order such that if an individual refuses to uphold a decision by a group, commune or council, the ability to opt out and find a more amenable assembly of folks is available.

These innovations seem good first steps in turning democracy from a worthless antiquity to a workable principle within anarchist theory, and as such should be encouraged and studied.

THIS: My essay regarding the organizational form and its various moments of domination, “The Organization’s New Clothes,” was first published in February of 1989 (and republished in 2015), and I see no reason to redact any portion thereof. (5) That critique, therefore, resonates throughout the following discussion, though time and space prohibit using it in any way other than as a critical prism. The “commune” is a scrambled term. It’s origins lie in the smallest administrative entity in France, the commune—corresponding roughly to a municipality. The word itself is derived from the twelfth-century Medieval Latin communia, meaning a group of people living a common or shared life. Which as a point of departure is interesting as the concept, even then, implied some degree of autonomy, both political and economic. It was, however, the Paris Commune during the French Revolution (1789 – 1795) that wrote the term in large red and black letters in the book of revolution. The Communards, in that first great explosion, distinguished themselves by their intransigence and demands for the abolition of private property and social classes. Eventually earning themselves the nickname enragés (“the enraged ones”). The revolutionary commune then has a subversive nature. It is dangerous. It is always dangerous when humans interact beyond the terrain of Capital and state, or in opposition to them.

Throughout the 19th Century the term commune, outside the administrative network of France, came to be associated with socialist and communist experiments and in a looser sense with all manner of utopian projects and communities—Owen, Fourier, Oneida, Amana, Modern Times… A slump for a few decades through the first part of the twentieth-century, then to confuse things further, the 1960s happened. The definition of the word “commune” ends for many North Americans somewhere in 1972; a tangerine swirl of bad acid, free love, and the Manson Family.

Which is not to say that there weren’t some important projects; among the more interesting was the West Berlin-based Kommune 1 (1967-1969), and Wisconsin’s contribution to utopia, Dreamtime Village. There have been thousands (likely tens of thousands) of communes over the past two centuries, intentional communities, collectives, cooperatives each with its own “glue”—the stuff that brought people together and “stuck” them to one another. In most cases this glue has been a mix of politics, anarchism, communism, utopianism, religious sentiment (usually wacky), livelihood, necessity, drugs, sexuality, or just plain detesting the dominant culture.

So what, exactly, is a commune? Who the hell knows? The problem is not the vagueness with which the commune is understood; rather it’s the lack of theory (and experience) that would provide nuance and clarity to this vagueness. The idea of the commune has been lost or diluted as a result of it’s own jangled historical context and the easily recuperable forms that it has recently taken. Ultimately, very much like democracy, the commune seems a quaint and faded relic in the cabinet of anarchist theory; filed under “V” for vestigial.

THAT: As above, so below. My own interaction with the Commune spans several articles on the Paris events of 1871, and includes my ongoing engagement with the conundrum of anarchist organization. All of my interactions with the concept of organizations operating in a revolutionary milieu had been on paper—in theory—up until the time I crossed into the Kurdish Autonomous Region. Then things changed.

The commune and council meetings I attended were varied. From an ad hoc encounter of a team of YPG militiamen near the Turkish border in Kobanî Canton, to a council of the Şehid Kawa C commune, to a ceremony and meeting between TEV-DEM representatives of Kobanî and Cizîrê Canton. In each instance I recall a series of similar impressions. First each encounter was characterized by a sense of purpose, of meaning. The attendees seemed clear that what they were engaged in, the simple task of meeting together, as a commune, as a team of YPG fighters, carried within it a seed, a moment of one possible future, for Northern Syria, perhaps for the planet. Many people commented on this when I asked their thoughts regarding these political forms. One woman I met in Paris at an HDP rally put it best, “We are here reinventing politics, in fact, the world.”

This perception, which could easily fade into arrogance, in these attendees seemed to produce a different mindset, quiet determination. These folks were not wealthy, they worked hard in an area where there was little work. The men’s faces were lined and etched with long hours spent under the harsh gaze of a Middle East sun. The hands of the women were simultaneously delicate and rough, while they carried callouses and cuts, they also carried the scent of lotion and perfume. The voices, gestures, and faces of the revolutionaries during the meetings were intent, searching, serious. There was kindness, hugs for a developmentally disabled young adult, a moment spent with a mother who had lost a son in the siege of Kobanî, and respect—as each person spoke to the accompaniment of silent nods from their peers.

Hope was also present, a quantity that history has so long denied to anarchists, and which some of us have reclaimed—not as an eventuality, but as a birthright. These folks believed they could change their lives, their community, many believed they could change (and were changing) the world.

Finally, and most importantly, in each of these meetings there was an overwhelming sense of the banal. These were folks who, when they mentioned the cantonal authority at all, referred to it laconically as the anti-government, or the anti-regime. They had seen and participated in sweeping social changes and experimentation and in the process it had become commonplace, like lunch. This is not to say that there was no joy in the proceedings, far from it. Rather what was really missing was fear, and in this sense the social revolution in Rojava may truly be said to have passed into a phase of maturity and permanence. The sole caveat in the short-term being the defeat of Daesh.

Some theorists have been advancing on the idea of the commune, but from strange directions, post-left directions. Peter Lamborn Wilson in TAZ: The Temporary Autonomous Zone and Pirate Utopias forces the issues of time and failure/success and the commune. He rejects utterly, as we must, the technological reasoning that the longer a commune exists the better or more successful it is, or was. In TAZ he specifically provides a formula for a new idea of a commune, a temporary encounter—perhaps hours, perhaps minutes—characterized by conviviality, joy. This encounter is also autonomous in that it is as independent, and free of the fetters of Capital and state as possible. This is essential to understand. The commune is combative, not subservient. That is the basis of its autonomy.

As opposed to bounding the definition of the commune or even trying to refine it, I believe that defocusing on the concept seems a sound strategy. I would argue that whether it is a phalanstère with all the Fourierist fauna intact, or a meeting between friends to relive old times, or to create new ones; it doesn’t matter—it is a commune. Why bound something, why hem something in when it presents itself as a viable model for organization? Rather, without a definition, moving with tiny baby steps towards an understanding of what works and what is useless in the commune model. That strikes me as one promising, potential direction towards both engaged social experimentation and ruthless social contestation

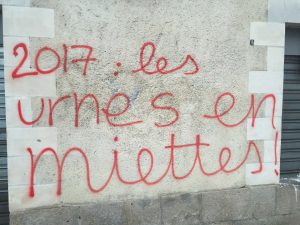

Finally, and at a macro-level the concept of federalism may make a theoretical comeback. If the commune model makes any sense at all, then federalism isn’t very far behind. This returns anarchism to its philosophical roots, Proudhon especially, but also Pi i Margall, and Bakunin. The insurrectionary potential for federalism seems vastly underestimated. The movement to section society into smaller and smaller units, the federation of these units by mutual agreement, and the potential for economic cooperation and shared self-defense these units offer make of federalism a potentially daunting, though rather  blunt, instrument. Note here that the current usage of federalism being the nation-states accumulation of power, wealth, knowledge…. ultimately producing the ability to control and dominate subject populations; is, in effect, the opposite of the concept’s standard historical definition. It is Pi i Margall, the non-anarchist grandfather of Spanish anarchism, in his 1855 work La Reacción y la Revolución who will offer the final word on the potential of federalism, “…the constitution of a society without power is the ultimate of my revolutionary aspiration[s],” stating he would, “divide and subdivide power,” until, “I shall destroy it.”(6)

blunt, instrument. Note here that the current usage of federalism being the nation-states accumulation of power, wealth, knowledge…. ultimately producing the ability to control and dominate subject populations; is, in effect, the opposite of the concept’s standard historical definition. It is Pi i Margall, the non-anarchist grandfather of Spanish anarchism, in his 1855 work La Reacción y la Revolución who will offer the final word on the potential of federalism, “…the constitution of a society without power is the ultimate of my revolutionary aspiration[s],” stating he would, “divide and subdivide power,” until, “I shall destroy it.”(6)

The formation of communes also seems a viable real world strategy in that it fulfills two immediate functions—first they can act as support, a backbone for the movement of militants quickly to areas where their services might be required. In this way they may function very much as the book stores, infoshops, and alternative spaces did in the anarchist milieu of the past several decades in the US, or as the communes did in Kobanî during the siege. Their resources can assist in the provision of shelter, food, medical aid, and comfort for fighters. The communes can also provide valuable intelligence on local conditions, law enforcement, and assist in identifying those specific targets most noxious to the community. Put in contemporary military parlance, the commune may not be a weapon, but it can function as a weapons platform for the mobile anarchist fighters. Secondarily, the communes provide for the sedentary members of the milieu a laboratory, a setting in which to experiment with new ideas, new forms, coalescing, in protoplasmic form, the seeds of revolutionary institutions yet to be. Communes are nurseries where budding insurrections are reared. Ancillary to this effect, yet no less important, is the possibility that communes will help to shrink the attrition that has plagued anarchism since its inception as a political movement. A life dedicated to liberty is difficult to sustain, and most anarchists eventually succumb to the Cthulhu call of new cars, big houses, and squandered lives. At the age of 55, I have seen thousands of anarchists come and go, only those too stubborn, or too anti-social, like my friends, and myself seem to remain. Communes may stem this drift by producing a social milieu that is amenable to the various vagaries of the anarchist personality type, and by distributing resources for assistance with the real world issues of food, shelter, childbirth and rearing, loneliness, illness, old age and death.

The commune is a verb. The commune is a question.

THE OTHER THING

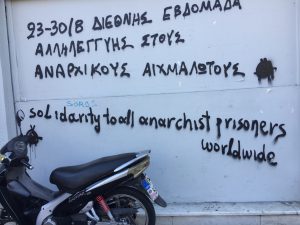

Anarchism has, rightly, been adrift since the end of the Second World War. With little understanding of its roots, history, and struggles most of us did the best we could with what we could find. There were no organizations to criticize or join and it was difficult enough just to find anarchists in NYC in 1984. We were orphans. The situation has changed, there are more anarchists, they are more easily contacted and the explosion of information has given us our story back. As a confluence, the news out of Greece, Rojava, Europe, in fact just about everywhere seems to be turning in our direction. Those in the milieu, therefore, have some choices to make. Where to place energy, where to invest time and effort, in a word—what to do? There are, at a minimum, as many possible answers to this question as there are anarchists now alive. As my response, I’ll state the following…

Form Democratic Communes.

Federate.

Be Ready.

NOTES

- La Boetie, Etienne (1975) The Politics of Obedience: The Discourse of Voluntary Servitude. Montreal; Black Rose Books.

- Vaneigem, Raoul. (1994) The Revolution of Everyday Life (Donald Nicholson-Smith, Trans.). London: Rebel Press

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. (1867-1870) Oeuvres completes de P-J. Proudhon. Paris: A. Lacroix, Verboeckhoven et Cie.

- Ocalan, Abdullah (2011). Democratic Confederalism (transl. International Initiative). Transmedia Publishing Ltd.: London, Cologne.

- Simons, Paul Z. (2015). “The Organization’s New Clothes” Black Eye: pathogenic and perverse. Ardent Press, Berkeley CA

- Pi y Margall, Francisco. “Reaction and Revolution,” in Anarchism, A Documentary History of Libertarian Ideas, Volume One