By El Errante

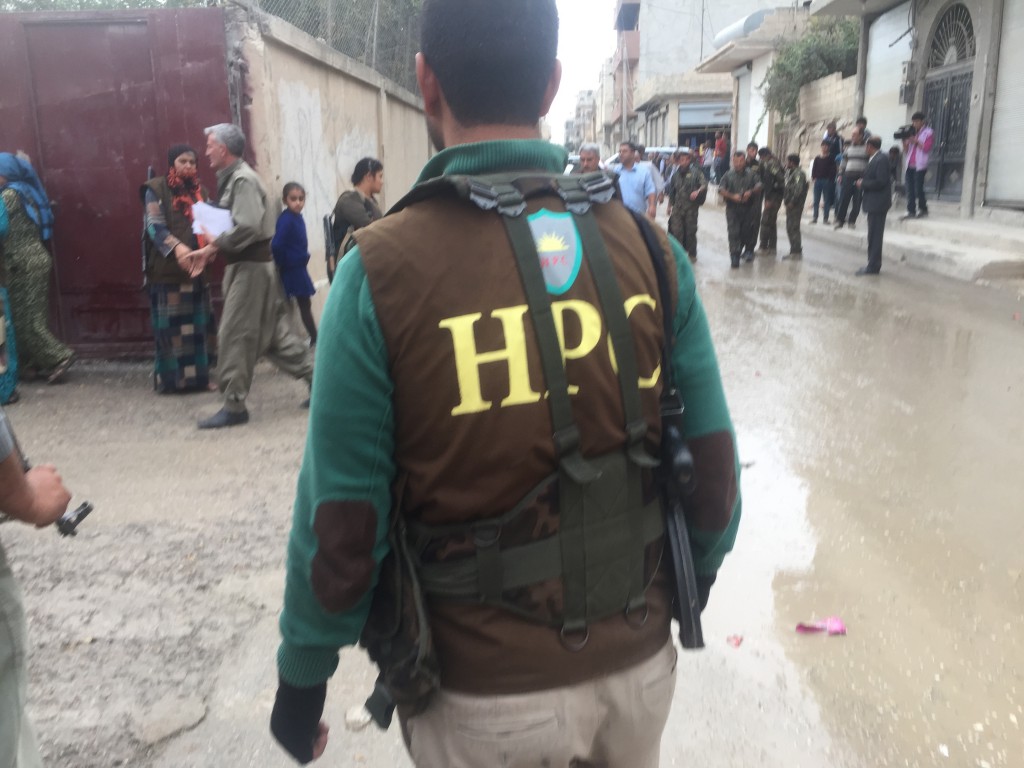

The two Hyundai minivans cruise caravan style through the backstreets of Kobane. In the first van are two representatives of the Kobane Canton’s TEV-DEM, the body charged with implementing Democratic Confederalism. In the trailing minivan I ride with the translator and driver. Tiny children play on either side of the street and seem ambivalent to the passing cars, if they can survive a month long siege by ISIS, a few stray cars are nothing.

I had met Ahmad Shaif at the Kobane Canton Center, a bullet-pocked building set on a hill in Kobane. In previous years it had been the government center for the Syrian state and was subsequently expropriated by the Kurds after the representatives of Assad’s regime exited the canton post-haste. Ahmad is one of several TEV-DEM administrators, and his office bare of paperwork, computers or any other item one would associate with a workspace in the West, is the place where Kobane residents come to for assistance in maintaining their communal councils. We had met and he had invited me to a council commune meeting he was helping to facilitate. I was in, definitely in.

Our vehicle stopped on a side street and an older man greeted us, hands shook all around, I was introduced and welcomed. We went through a rubbled courtyard and up a flight of steps. Shoes were kicked off, and we entered into a room fully carpeted with cushions spread sofa-like around the walls. A window opened onto the room and several bullet holes impinged the glass, these projectiles had traced a neat line of holes into the concrete of the far wall. Above this damage, a picture of Ocalan was hung, draped on either side by YPG and YPJ flags. The room started to fill with men, most older and Kurdish, and one or two Arabs. Women slowly joined the group as well, the older women, their heads swathed in scarves, would take turns shaking hands around the room and then sit. Men and women sat apart, the empowerment of women not yet extending to the predefined Middle East cultural space.

Mr Shaif began saying that it was a pleasure to be welcomed by the council, and that he was happy with the number of people attending (18 total, 10 men, 7 women—and me). He then drew out a map and laid it on the carpet, pointing to a block in a tangle of lines and circles meant to represent the Sehid Kawa (Martyr Kawa) neighborhood of the city. He continued that with the recent influx of immigrants into the city they were expecting the commune to expand, and that if it grows larger than 100 families it may be too unwieldy to be responsive. Possible geographic divisions were discussed with the council; a few questions, a few answers, some leaning over the map and nodding. He finished by saying that the division of the commune, if any, was up to them. He wanted to present the issue and whatever they decided was fine. Just call with an answer.

I was introduced and got a chance to ask a few questions. I asked about what they do, on a regular basis, as a council and got a wild range of responses, from dealing with marital issues, helping get gas and rides to and from clinics, shopping, whatever was needed, whatever was urgent. Finally a man said that during the siege it was the council that had kept the commune fed and clothed, that helped with YPG intellingence gathering and that when the fighting became desperate commune members were issued Kalashnikovs and fought with the YPG to save their neighborhood. I asked if all were given weapons, including the women. He nodded and said everyone willing to fight, fought.

My curiosity got the better of me and I asked about the line of bullet holes in the wall. The man who had initially welcomed us stood and pointed out the window to a two story building some 200 feet away. Pointing, he indicated the line of sight between the buildings top floor and the damaged wall in his house. Then holding an invisible Kalashnikov he sighted the building and pretended to shoot back. Saying that he had returned fire and that the gunman had eventually left.

With my questions done they asked me what the Americans thought of Kobane. I said many supported their Revolution, many wanted to hear more, and those ignorant enough to have an opinion without information didn’t matter. There were some smiles and nods—especially the women, a few seemed surprised at my directness. Finally a young woman of fifteen asked me what I thought. I closed my eyes for a moment and said, ”What’s happening here may be part of the future, not just for the Kurds, but for everyone. I know I feel welcome here, and safe. And as small as that is, it’s a big change from much of my experience.”

Ahmad then rose and thanked the group, we all shook hands again—there were some touching of hands to the chest, and we left.

Back out on the street the children were busy playing, somewhere a dog barked and the drivers were cranking over the vans engines. I stopped Ahmad and asked about how the communes had formed, did TEV-DEM have responsibility for that task. He shook his head, “Some formed spontaneously, some we helped get started, many have yet to become stable, with strong council members. It’s a process, and in Kobane the siege speeded up the formation of the communes, but the rebuilding and lack of resources has now slowed it. We can’t stop though, these communes are at the center of society.”

He nodded and left. I climbed into the van and set out for my hotel, some coffee and to think through this thing. This new thing.

(The name of the commune, Sehid Kawa C (Martyr Kawa C) is derived from the name of the neighborhood in Kobane — Sehid Kawa and C designates it as the third commune formed. Many of the city’s areas are being renamed for the YPJ/G fighters who were killed in those respective neighborhoods. Martyrs, their lives and deaths form a large part of Kurdish resistance consciousness and symbolism. More later….)