What Were You Thinking Of…

When You Dreamt That Up?

–Echo and the Bunnymen

It is 1988.

It is August.

It is the Beginning of the End.

In a dark room five figures move around a table, they talk, three smoke. A piece of paper is drawn through a typewriter. One figure sits and leans forward, the smacking of typewriter keys echoes around the room and slowly words roll out onto the paper…

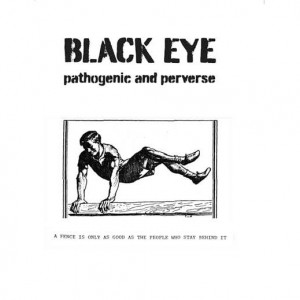

BLACK EYE was born pathogenic and perverse in a basement in the Lower East Side’s Heart of Darkness. Half a dozen comrades armed with even fewer weapons (besides pens and typewriters, a few cartoons and quite a few ideas) set out to upend this rotten yuppified, spectacular world and provide first-hand reports of its demise. Initial articles ranged from paganism to the poverty of student life to the confessions of an ex-Trotskyist. Fiction and poetry complement revolutionary theory and resurgent utopianism. Eclecticism continues to be a virtue, is desired and cultivated, a political gesture itself in an era of heterogeneity. The common ingredient is liberation.

The malcontents responsible for this rag are lust-crazed maximalist freedom fighters, ornery and virulently independent squatters, latter day rock and roll Jacobins and potentialities seeking to impose their unique Frankenstein monster egos on an unsuspecting America oblivious to its own decomposition. It must be admitted: BLACK EYE was founded by anarchists.

At the very heart of the problem, if not near to it, one encounters Leftism, in its Liberal to Leninist variants, and institutionalized opposition, part and parcel of the dominant culture. The BLACK EYE folks recognize Right and Left as two sides of the same ugly coin and say don’t take any wooden nickels and DEMAND MORE THAN SPARE CHANGE! The complicity of Leftism must be exposed. We refuse to forget the unforgivable or forgive the unforgettable.

The domination of the specialists will come to an end. Publishing is a good place to start. BLACK EYE publishes those who never fancied themselves writers, plagiarizes blatantly from all manner of texts, and snatches material circulating through the mail or mouthed by frenzied poets in New York City. BLACK EYE sneered at offers of word-processing and desk-top publishing and the concomitant smorgasbord of computer generated stylistics in order to demystify information and argument. “Hey I can do that!” With a few bucks, a typewriter and a xerox machine, anyone can be a modern Tom Paine, celebrating their opinions, communicating with others. BLACK EYE does not seek to “grow” and pities those held captive by economistic and productivist outlooks. Instead we hope to see similar projects initiated by others everywhere and all over our post-industrial landscape. We think that this will be an important step in people beginning to think for themselves again.

BLACK EYE wants to corrode all your received ideas and cherished ideological assumptions. It will give you a black eye if it doesn’t open your eyes, and it might just set you on an adventurous path of zero-work role refusal and you’ll discover you’re a voluntary conscript in an army of conscious egoists practicing the permanent revolution of desire.

BLACK EYE is a proto-council of the marvelous.

BLACK EYE asks, Why not?

It is 2014.

It is August.

It is the End of the Beginning.

If the foregoing text wasn’t really written that way, it should have been. During the ’80s and ’90s there were a million zines. They came in all colors and flavors. Some were political, some were erotic, some were awful. Most are about being pissed off at someone or something. Who knows how these things start? Someone somewhere finds that they have a few extra reams of paper, they type up a few ideas, maybe steal some artwork and paste and copy and staple for a few hours. Friends get copies in the mail, strangers find them on the floor of a bus. They are thrown away; they are cherished. Pretty soon everyone is a publisher, an editor, a critic, a writer, and a clown; or at least they could if they wanted to. And that is what fueled the global zine machine. The possibility; the dangerous, stormy potential.

In spring of 1998 I had just been through a nasty breakup and with $2,000 in my pocket went South of the Border to drink, sun, and with any luck, kill myself; well, two out of three ain’t bad. I returned to NYC in July of 1988 and found that a few friends and malcontents who hung out at the Anarchist Switchboard had put enough material together to crank out an issue of a zine they called Black Eye. I had returned from Central America with sufficient diary and travelogue copy to pitch in an article for the next few issues. And that’s how I found my way into the weird and wonderful world of zines.

The production of Black Eye was a work of love. Graphics were stolen from other zines, canned graphics books lifted from art supply houses, things found on the street, advertisements, doodles. Each writer was responsible for their own copy so the zine had a mind-bending array of fonts, sizes, smashed typewriter keys and sometimes just plain pen on paper was used. Usually just one of us took responsibility for pasting an issue together and then we would all take turns copying the pasted sheets. I don’t know how many millions of free copies I stole from my various places of employment. One of us worked in a stationery store with a xerox machine in back—thousands more pages were churned out there. Finally if no one could steal anymore copier time we went to Kinko’s and paid for the last few copies—it was worth it.

Black Eye came out in print runs of 500, with the one exception of the Tompkins Square Park Riot edition (Issue #3); we’ll get into later. St. Mark’s Books would take a few copies, we’d all try to sell copies to people better off than we were, some we would give to friends—hundreds we would trade through the mail, which was another great secret of the zine world. As chaotic and fluid as the whole scene was, there was one central touch point, Factsheet Five (FF), a quarterly that came out of California and later, New York. Originally the brainchild of Mike Gunderloy and in the beginning years covering only sci-fi fanzines, by the late 1980’s FF contained reviews of literally thousands of zines. We would look through Factsheet Five for other zines that interested us and we would trade with them. The zine universe was an underground hive of activity, discussion, character assassination, and argument fueled by the US postal service.

Black Eye set out initially on a course of anarchist theory, fiction, and some personal reflection as in the “Diary of an Ex-Trotskyist” and the short story “Puppy and Kitty Prison” in Issue One. Graphics played an important part of Black Eye and we used detourned cartoons, free hand drawings and stuff stolen from other zines. We learned quickly that high contrast pen and ink worked much better than gently shaded images, so no Hokusai in Black Eye, but a lot of comics.

Black Eye was very much a “local zine” during this period, concentrating on issues of squatting, homelessness, NYC Police Department barbarity and anything we could cull from word of mouth. Then between the second and third issue the unreal happened. The City of New York decided to impose a curfew on Tompkins Square Park in the heart of the Lower East Side and a few blocks from both the squats and the Anarchist Switchboard. It was a ridiculous idea back then, few people had air conditioning, and things only cooled down in the city late at night. Further, because of the various ethnicities in the neighborhood, Puerto Ricans, African Americans, and punks spent much of their day at night, specifically in the park. I remember one evening strolling home from a debauch at about four am and seeing two old men playing dominoes on one of the park’s benches. The first night of the curfew was to be August 8th and all hell literally broke loose. The riot lasted until 2 or 3 am and everyone was involved, little old ladies got water for the rioters, local tavern owners joined with patrons to beat on police officers, and wave after wave of cops tried to maintain order. The next day the city backpedaled hard and fast, withdrawing the curfew. The press roasted Mayor Koch and especially Gerald MacNamara, the commanding officer of the police forces. Especially when it turned out the entire event had been filmed and showed that cops had hidden their badge numbers to avoid official reprimands and that they had attacked first. Score Anarchists/Squatters/Lower East Side Residents, One—NYPD, Zero. We put everything we could find about the riot into Issue 3 and offset printed 3,000 copies and sold almost all of them. It all culminated in one scene for me when two short little legs came easing down the steep steps of the Anarchist Switchboard, it was Allen Ginsberg come to see what we were all about. The next several issues maintained the action orientation of the zine and covered the issues of squatting, gentrification and the attempts by housing cops to throw out the trespassers. A number of the writers participated in the continental gatherings and major protests, in Philadelphia and Washington DC and these were reported on in the journal.

The other global event that Black Eye found itself having to respond to was the fall of communism in Europe and the Tiananmen Square protests and riots. I remember watching the Berlin Wall falling on television and hearing the news reporter just crow over the fact that the East Bloc had decided to participate in the “Free Market.” I kept thinking to myself I wonder what hell is really going on? The answers were not long in coming, Black Eye had excellent contacts in Poland and elsewhere in the Communist Bloc through Neither East Nor West, a magazine published New York and very soon we heard that the desire for new Levi’s was a tertiary issue. People were fed up with being treated like pawns in the grand communist game; they were tired of being numbered, oppressed, tortured—the spark was freedom (as the Russian underground press samizdat makes clear), not access to expensive clothing and the yuppie lifestyle.

As time went on theory began to play a larger role in Black Eye and in many ways where anarchist theory is at in the United States in 2014 is where the writers from Black Eye progressed to over the issues through 1993. Black Eye writers hated the “Left,” hence there was a truly strange mix of anti-civilization, feminist, insurrectionary theory in the issues of Black Eye. The topics that these issues were hashed out in were occasionally nutty, in one essay on Vietnam Major Bellows reviews US foreign policy choices in Indochina and arrives at individualist anarchism. Edwin Hammer’s articles consistently critiqued the cookie cutter roles that civilization imposes of its actors. In one of my pieces I develop theses defining the activity of play in culture, politics and economics. Debates were rare among the writers, everyone seemed interested in their own realm of theory though Sunshine D. and Mary Shelley actively debated feminism in two issues, neither one giving an inch of ground. Though I think Mary got the last word in. A number of pieces were lifted from other zines and books that interested us. One notable example is a humorous and effective piece by bp ummfatik titled “Take Things From Work.” I can only assume that bp ummfatik is a nom de guerre. Suffice it to say with the death of the Left, the Black Eye writers were left to their own devices to try to make some sense of civilization. In this feeling one’s way through the theoretical dark, some thinkers and activists appeared to show the way,

We quickly found ourselves interacting with an eclectic mix of earlier theorists. Jacques Camatte, one-time amigo of Amadeo Bordiga and member of the Italian ultra-left communist tendency, proved to be an extremely important thinker and thanks to Fredy Perlman much of his most important material was available in English. Camatte had shown that Capital had effectively superseded the law of value and that through the global dominance of the wage relation that the human species had been effectively proletarianized as of the end of the Second World War. Both findings are central to the foundation of post-left anarchism—the death of class conflict, the triumph of Capital over the law of value. Perlman himself, while not essential, has also proven to be an interesting and original thinker. Post-modernism was never really explored nor utilized by any writer, though Baudrillard’s Mirror of Production, is still an important essay and probably the final nail in the coffin of Marxism. John Zerzan’s material, particularly the essays in Elements of Refusal proved to be seminal in identifying just what the anarchists were up against, civilization itself. Though no writer ever published an explicitly anti-tech piece, his work instilled in most of us a healthy distrust for the ideology and effect of technology on the species. The Situationists made their entrance into the general American consciousness via Ken Knabb and his Situationist International Anthology, which was given to me by my boss at work. He had bought it and read it and he was no radical. It was just the book to read at the time. The jangled theoretics of the group, which derived as much from Hegel and Fourier as they did from Marx, were occasionally breathtaking and many of us used their argumentative models to develop our ideas. We stole liberally from history and historians which fueled many of my pieces on the Jacobins (Crane Brinton), the Fascists (Alice Yeager Kaplan), Progress (Georges Sorel), and Organization (Jacques Camatte). We read and were alternately interested and angered by the Frankfurt School. Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment is central to an understanding civilization as it appears today, Marcuse’s work on the psychology of Capital (The One Dimensional Man) is the last word on alienation. No book written since has even come close to his rigid and critical eye when it comes to suffering, loneliness, and powerlessness in a civilized world. Marcuse also did an amazing job discussing Hegel (Reason and Revolution: Hegel and the Rise of Social Theory) and revolution in one of his earlier works, though no one reads that now, as Hegel via Fukuyama has become the mascot of decadent Capital. Major Bellows attacked Fukuyama and I think did a good job critiquing the silly assertion that history stopped at the Battle of Jena. Everything was fair game and I believe that few political zines were as eclectic or as snarltooth as Black Eye.

So what was Black Eye? Basically a lot of fun. Black Eye was a group of friends trying to figure it all out in a place of conviviality and support. Black Eye did its best to push post-left anarchism front and center, to make people aware that the with the death of the Left, Life gets better, the chances for insurrection become more clear and the ways and means to produce a human community that realizes the talents of each of its members develops as a real possibility. Black Eye was hard work, we met weekly and I spent many Sundays as a Xerox ninja, as did Edwin Hammer, Joe Braun, et al. In the end it was worth it. I have gone on to write and edit several magazines, other collective members run art spaces, and one is still cranking out top-notch essays. And I will say I miss the whole thing, the late night discussions at the Veselka or Kiev restaurants, the smile of a friend as I discuss some crazy theoretical gymnastics, and the pride of holding a hundred hot-off-the-xerox-machine Black Eyes in my hands as I go to sell them in Tompkins Square Park. But that was then, this is now. Our ideas still resonate with much of what the Social Enemy has up its sleeve, but new theorists are needed as Capital and the nation-state become ever more fearsome adversaries in the battle for real freedom.

So I dedicate this Black Eye anthology to those of you who would take up the sword or the pen and make the writers and thinkers of Black Eye look like senile old reactionary codgers, for those willing to do so, the future is yours…

-Paul Z. Simons Order Black Eye through the LBC web site