Jason McQuinn

Jason McQuinn

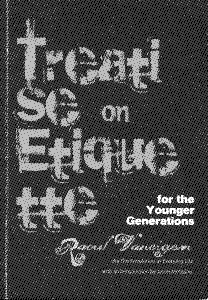

(Note: The following essay was written as an introduction to the 2012 LBC Books edition of the 1983 Donald Nicholson-Smith translation of Traité de savoir-vivre à l’usage des jeunes générations under the new title of Treatise on Etiquette for the Younger Generations.)

Raoul Vaneigem’s Treatise on Etiquette for the Younger Generations has, despite its epochal importance, often been overshadowed by Guy Debord’s equally significant Society of the Spectacle. And Vaneigem himself, along with his wider insurrectionary and social-revolutionary contributions, has too often also been overshadowed by Debord’s very successfully self-promoted mystique. As a result Vaneigem’s contributions have been rather consistently underappreciated when not at times intentionally minimized or even ignored. However, there are good reasons to take Vaneigem and his Treatise more seriously.

The Situationist myth

A half-century ago in 1967 two related books appeared, authored by then-obscure members of the Situationist International (hereafter, the SI). Each has made its permanent mark on the world. On the one side, a slim but dense book, The Society of the Spectacle,¹ appeared under the authorship of one Guy Debord – an avant-garde film-maker, but more importantly the principle theorist and organizer from its earliest days of the tiny “International” of curiously-named “Situationists.” On the other side, a how-to book on living “for the younger generations,” describing a surprisingly combative “radical subjectivity” in extravagant and often poetic language. The latter was originally entitled Traité de savoir-vivre à l’usage des jeunes générations, but was initially translated into English as The Revolution of Everyday Life,² appearing under the authorship of Raoul Vaneigem. Both books exemplified a savagely critical and creatively artistic, historical and theoretical erudition rare among the usual offerings of the then still new New Left. But stylistically the books could hardly have been more different, though they ostensibly argue for the same end: inspiring the creation of a social revolution which would both destroy capitalism and realize art in everyday life!

A half-century ago in 1967 two related books appeared, authored by then-obscure members of the Situationist International (hereafter, the SI). Each has made its permanent mark on the world. On the one side, a slim but dense book, The Society of the Spectacle,¹ appeared under the authorship of one Guy Debord – an avant-garde film-maker, but more importantly the principle theorist and organizer from its earliest days of the tiny “International” of curiously-named “Situationists.” On the other side, a how-to book on living “for the younger generations,” describing a surprisingly combative “radical subjectivity” in extravagant and often poetic language. The latter was originally entitled Traité de savoir-vivre à l’usage des jeunes générations, but was initially translated into English as The Revolution of Everyday Life,² appearing under the authorship of Raoul Vaneigem. Both books exemplified a savagely critical and creatively artistic, historical and theoretical erudition rare among the usual offerings of the then still new New Left. But stylistically the books could hardly have been more different, though they ostensibly argue for the same end: inspiring the creation of a social revolution which would both destroy capitalism and realize art in everyday life!

[pullquote]“In a society that has abolished every kind of adventure the only adventure that remains is to abolish that society.”[/pullquote]

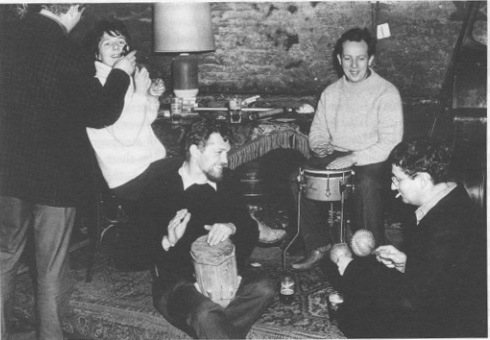

Only a short year later the anarchistic (though fairly incoherent) March 22nd Movement and the charismatic “Danny the Red” (Daniel Cohn-Bendit), along with a small group of more coherently-radical, reinvented Enragés (who were protégés of the SI), helped incite spreading student protests, initially from the University of Paris at Nanterre to the Sorbonne, and then throughout France. A protest that soon led to the tumultuous – now semi-mythical – “May Days” as student strikes and street protests were amplified by a huge wave of wildcat strikes that became a general strike and severely threatened the stability of the Gaullist regime. Situationist themes more and more frequently appeared in this social ferment. They were expressed not only in SI books and pamphlets, but most importantly through increasingly widespread graffiti, posters, occupations and other interventions. “Power to the imagination.” “Never work.” “Boredom is counterrevolutionary.” “Live without dead time.” “Occupy the factories.” “It is forbidden to forbid.” “In a society that has abolished every kind of adventure the only adventure that remains is to abolish that society.” “I take my desires for reality because I believe in the reality of my desires.” “Under the paving stones, the beach.” Wherever one looked the SI’s slogans were urging the rebellion forward! While most other supposedly “radical” groups were peddling the same old (or the same old “new”) leftist lines and rituals which usually, like the Stalinists in the French Communist Party, amounted to urging restraint and respect for their leaderships. Or at most, the urging of politically-correct, “responsible” agitation, respecting the limits of directly democratic procedures which tolerated the inclusion of Leninists, Trotskyists, Stalinists, Maoists and liberal reformists of all types, guaranteeing their incoherent impotence.

Only hints of social revolution were really ever in sight during the May Days, despite the recurring waves of violent street demonstrations and the widespread students’ and workers’ occupations that culminated in the massive (but in the end, frustratingly passive) general strike across France. However, even hints of social revolution are never taken lightly, as otherwise sober governing bureaucrats began to panic, and at least the thought of revolution began to be taken seriously by the general population. A survey immediately following the events indicated that 20% of the French population would have participated in a “revolution,” while 33% would have opposed a “military intervention.”³ Charles De Gaulle even fled at one point for safety in Germany before returning to France once he had ensured the backing of the French military. These hints of revolution were especially powerful when much of the world was watching while experiencing its own various waves of anti-war protest, constant student and worker unrest, and a creative cultural contestation that at the time (throughout the 1960s at least) had as yet no very clear limits. Then it all quickly evaporated with the excuse of new national elections welcomed by all the major powers of the old world in France: the Gaullists, the Communist and Socialist parties, the established unions, etc.

As it turned out, in the 1960s most people in France, like most people around the world, were not ready for social revolution, though a few of the more radical of the French anarchists, the Enragés and the Situationists had made a decent effort to move their world in that direction. In the end, neither the more radical of the anarchists nor the Enragés and Situationists proved to be up to the task. And the historic trajectory of radical activities through the ensuing half century is still grappling with the question of just what it will take. But it remains hard to argue that, among those who even tried, it wasn’t the Situationists who were able to take the highest ground in those heady May Days in 1968.

The Situationist Reality

The Situationist International, created in 1957, was a grouping of various artists from a number of tendencies – influenced by Dada, Surrealism and the Lettrists – who to one degree or another wished to suppress art as a specialized activity and realize art in everyday life. The group published a journal titled Internationale Situationiste from its beginning, founded by Guy Debord, who was the dominant (and sometimes domineering) personality within the organization. At first, the Situationist emphasis was largely a continuation of the radical Lettrist investigations into filmmaking, psychogeography4 and unitary urbanism,5 including the development of a theory and practice of creating situations, in conjunction with the practice of dérive (unplanned drifting, following the influences of one’s environment) and détournement (a practice of subversive diversion, reversal or recontextualization of commoditized cultural elements). But the membership changed frequently, sometimes drastically, over the life of the organization with exclusions and denunciations becoming far more the rule than the exception. And with the changes in membership came changes in emphasis and direction. Of the original founders only Debord himself was left at the dismal end.6

Fairly early on there was an increasing split between those pushing more and more to radicalize the organization under the leadership of Debord (who after 1959 abandoned his own filmmaking for the duration), and those who intended to continue functioning as radically subversive, but still practicing, artists – like the Danish painter and sculptor Asger Jorn, his brother Jørgen Nash, the Dutch painter and (hyper-) architect Constant Nieuwenhuys. The radical artists regrouped in a number of directions, including around Jacqueline de Jong’s Situationist Times, published from 1962-1964 (in 6 issues), and Jørgen Nash’s Situationist Bauhaus project, not to mention their influence on the Dutch Provo movement. The poetic-artistic radicals, on the other hand, continued the SI itself under the influence of Debord’s developing synthesis of Marxism and Lettrism. (Of note, a central player, Asger Jorn, left the SI in 1961. But as a good friend of Debord who continued to fund the SI, as well as being the companion of Jacqueline de Jong and brother of Jørgen Nash, his loyalties remained divided.) It was during and after the development of these original splits and the redirection of the SI that Raoul Vaneigem (in 1961) and most of the other non-artist radicals – including Mustapha Khayati, René Viénet,7 René Riesel8 and Gianfranco Sanguinetti9 – signed on to the project.

From its beginning the Situationist International fully embraced a practice of scathing critique and scandalous subversions. And at the same time, initially through the impetus of Guy Debord, the SI at least attempted to incorporate and integrate many of the more radical social ideas of the time into its critical theory. Before the SI appeared, the Lettrists had already become notorious for the blasphemous 1950 Easter Mass preaching the death of God at the Cathedral of Notre Dame by ex-seminary student Michel Mourre.10 The subsequently-organized Lettrist International (including Debord) launched its own little blasphemous attack on the aging cinema icon Charlie Chaplin in 1952, interrupting his press conference by scattering leaflets titled “No More Flat Feet.” By the time the SI had settled on its final radical trajectory, explosive events like the 1966-67 Strasbourg scandal – which culminated in the funding and distribution of 10,000 copies of Mustapha Khayati’s Situationist attack On the Poverty of Student Life11 by the University of Strasbourg Student Union – were inevitable. The massive SI graffiti, postering and publishing campaigns from March through May of 1968 can be seen as the culmination of this line of attack.

At the same time, the SI’s exploration, incorporation and integration of scandalously radical social theory paralleled its practice of subversive scandal. Although the backbone of Situationist theory remained Marxist, it was at least a Marxism staunchly critical of Leninist, Trotskyist, Stalinist and Maoist ideology and bureaucracy, and a Marxism at least partially open to many of the more radical currents marginalized or defeated by the great Marxist-inspired counter-revolutions experienced around the world. Along with the avant-garde art movements like Dada and Surrealism, there was room for at least the mention of a diversity of anarchists and dissident non-Leninist Marxists, radical poets, lumpen terrorists, and even transgressive characters like Lautréamont and de Sade in the Situationist pantheon. It can be argued that it was the coupling of its penchant for scandalous incitements with its shift from experimental artistic practices to developing a more and more radically critical theory that made for whatever lasting success the SI attained. Certainly, the creatively subversive gestures without the radically critical theory, or the radically critical theory without the creatively subversive gestures would never have captured imaginations as did their serial combination and recombination. It should also be noted that although the SI obviously was not the creator of the May Days in 1968 France, the SI was the only organized group which had announced the possibility of events like these, and which was actively agitating for them before they occurred. Although some pronouncements by Debord and other Situationists, and some comments by enthusiastic “pro-situationists”12 after the fact sometimes bordered on megalomania, at least there were reasons for misjudgments about the SI’s actual effectiveness. They were not merely figments of imagination.

The SI theorists: Guy Debord or Raoul Vaneigem

That the two most important theorists of the SI were Guy Debord and Raoul Vaneigem is indisputable. Of what their contributions (and their relative values) consisted is another matter. At first, during the heat of the struggles in France the meanings of their contributions were generally considered to be so similar as not to require much analysis. However, it didn’t take long – especially after Vaneigem left the SI in 1970 – for divergent lines of interpretation to form and attributions or accusations of “Vaneigemism” and “Debordism” to begin flying in some quarters. The pro-Debordists tended to emphasize the over-riding importance of Marxism to the Situationist project, along with a resulting accompanying emphasis on sociological analysis and critique of class society – centering on Debord’s concept of the spectacle. It was also from this direction that most talk of Vaneigemism seems to have come (in fact, I have yet to come across anyone claiming to similarly criticize Debord based on any ideas or analyses from Vaneigem). The so-called “Vaneigemists” seem to be lumped into this category on the basis of an alleged tendency to see potential signs of total revolt in minor or partial refusals within everyday life,13 along with a resulting exaggeration of the potentialities of radical subjectivity for the construction of an intersubjective revolutionary subject. At its extreme, the argument equates radical subjectivity with attempts at narrowly “personal liberation” or even bourgeois egoism, implying that any true participation in the construction of a collective revolutionary subject demands the complete subordination of one’s personal life to a rationalist conception of revolution.14 While the former argument would seem to be largely a question of emphasis (just how important can refusals within everyday life actually be for potential social revolutionary upsurges in comparison to mass sociological factors), the latter appears to verge on the negation of most of what is distinctive and innovative within the Situationist project! At the least these conflicts reveal an underlying tension that was never resolved within the SI.

[pullquote]This underlying tension between the sociological and the personal, between the idea of a collective or social revolutionary project and a revolution of everyday life, still remains the central unresolved problem of the libertarian social revolutionary milieu to this day. (The impossibility of including and incorporating any critique of everyday life in the authoritarian, bureaucratic and inevitably unimaginative mainstream left is one major reason for its own steady decline.)[/pullquote]

This underlying tension between the sociological and the personal, between the idea of a collective or social revolutionary project and a revolution of everyday life, still remains the central unresolved problem of the libertarian social revolutionary milieu to this day. (The impossibility of including and incorporating any critique of everyday life in the authoritarian, bureaucratic and inevitably unimaginative mainstream left is one major reason for its own steady decline.) The unfinished synthesis and critique of the SI is just one of many unfinished syntheses and critiques which litter radical history from 1793 to 1848, from 1871 to the great revolutionary assaults of the 20th century in Mexico, Russia, Germany, Italy, China and Spain. Certainly, as Vaneigem argues in his Treatise, there has to have always been “an energy…locked up in everyday life which can move mountains and abolish distances.” Because it is never from purely sociological forces that revolutions spring. These forces themselves are mere abstract, symbolic formulations concealing the everyday realities, choices and activities of millions of unique individual persons in all their complexity and interwoven relationships.

Despite Guy Debord’s increasing fascination with the austere, rationalistic sociological theorization revealed in the Society of the Spectacle, his entire commitment to the critique of art and everyday life, and his genuine search for new forms of lived radical subversion guarantee a substantial understanding of the central importance of Vaneigem’s work for radical theory. Still, though I know of no libertarian radicals who deny the critical importance of Debord’s work, there remain plenty who minimize, or even denigrate, the importance of Vaneigem’s. What is it in Vaneigem’s poetic investigations of the insurrectionary and social revolutionary possibilities of refusal and revolt in everyday life that so threaten these would-be libertarians? Could it be that these supposedly radical libertarians – whether “social” anarchists or some form or other of non-orthodox Marxists – may not be so different from the decaying mainstream left as they imagine?

Whereas Debord used his Society of the Spectacle largely to update Lukácsian Marxism by elaborating the sociological connections between some of the more important aspects of modern capitalism,15 Vaneigem sought in his Treatise on Etiquette for the Younger Generations to elaborate the subjectively-experienced, phenomenal connections between most of these same aspects of capitalist society. In Society of the Spectacle this meant Debord focused on: description of contemporary capital developing new forms of commodity production and exchange, the increasing importance of consumption over production, the integration of the working class through new mechanisms of passive participation, particularly the development of spectacular forms of mediation – communication and organization, and the overarching integration of these new forms of production and exchange in a continually developing, self-reproducing sociological totality which he called “spectacular commodity society.” Vaneigem’s innovation is the systematic description of these same developments from the other side, the side of lived subjective experience in everyday life: phenomenal descriptions of humiliation, isolation, work, commodity exchange, sacrifice and separation he has himself undergone or suffered, which help readers interpret their own experiences similarly.

Raoul Vaneigem and the revolution of everyday life

Raoul Vaneigem’s Treatise was a first, exploratory 20th century attempt at the descriptive phenomenology of modern slavery and its refusal.16 Through the Treatise Vaneigem urged rebellion against this enslavement through the refusal of work and submission, along with the reappropriation of autonomous desire, play and festivity. This phenomenology of lived rebellion was soon played out in the protests, occupations, graffiti, and the general festivity of the 1968 Paris May Days – within mere months of its initial publication. This is what makes Vaneigem still exciting to read a half century later.

A look at the wide variety of the most popular slogans and graffiti from the May Days in Paris – the ones that captured people’s imagination and gave the period its magic – makes it hard to ignore the fact that the emotional power they expressed (and still express) was based primarily on the excitement of the new focus on changing everyday life. And that Vaneigem’s Treatise was probably their most common source. Largely gone were the old leftist slogans exhorting workers to sacrifice for the advancement of their class organizations, to put themselves at the service of their class leaders, or to build a new society by helping class organizations take over management of the old one. Instead, people were exhorted to organize themselves directly on their own not only outside of the ruling organizations, but also outside of the pseudo-oppositional organizations of the left. And not with the relatively abstract political goal of building systems of Socialism or Communism, but with the here and now, practical goal of organizing their own life-activity with other rebels directly and without giving up their initiative and autonomy to representatives and bureaucrats.

This refusal of representation and bureaucracy, along with the emphasis on autonomous desire, play and festivity obviously has much more in common with the historical theory and practice of anarchists than with most Marxists. In fact, Marxists of the old left and the new will often be the first to point this out – and criticize it. But there still remains a surprisingly large area of crossover and cross-pollination between the multitude of creative, grass-roots movements, rebellions and uprisings within the broad libertarian milieu and some of the more libertarian-leaning of the minority traditions within Marxism. Of the latter, it was the council communists in particular, whose politics were largely adopted by the SI. And this is where the deep ambiguity of the SI is based. All of Marxism – including its dissenting minorities, and all of its myriad splinters, both mainstream and marginal – is fundamentally based upon the unavoidable sociological perspectives of species, society and class. All Marxism begins and ends with these abstractions. This is counter to the broad libertarian tradition, where actual people – with all their messy lives and struggles, hopes and dreams – are necessarily the center of theory and practice. This is the real “unbridgeable gap” – as the sectarians so love to put it. But it is between the ideologically-constructed, abstract subjectivity of reified concepts (like society and the proletariat) and the actual, phenomenal, lived subjectivity of people in revolt together. The SI was never able to overcome this divide. Nor was Vaneigem’s Treatise. But Vaneigem did make it farther than anyone else at the time in his text.

[pullquote]The only reason sociological investigations, analyses and theories can tell us anything beyond the most obvious banalities is the extent to which they reflect the dominant forms of enslavement in a society of modern slavery. “Scientific,” “objective” descriptions incorporating sociological explanations for mass human behavior depend upon predictable patterns of human action based upon broad social dictates of conduct, codified and enforced by institutions of domination.[/pullquote]

If it hasn’t yet ever been made clear enough, then now is the time to finally put to rest the necessarily ideological nature of any and every reified collective subject, whether religious, liberal, Marxist, fascist or nationalist, reactionary or revolutionary. And this isn’t a question of adopting a methodological individualism over a methodological holism. One or the other may or may not be an appropriate choice for any particular specific investigation or analysis, depending upon one’s goals. But beginning with a reality defined in terms of an abstracted species, society or class makes no more sense than beginning with a reality defined in terms of abstract individuals. The only reason sociological investigations, analyses and theories can tell us anything beyond the most obvious banalities is the extent to which they reflect the dominant forms of enslavement in a society of modern slavery. “Scientific,” “objective” descriptions incorporating sociological explanations for mass human behavior depend upon predictable patterns of human action based upon broad social dictates of conduct, codified and enforced by institutions of domination. They are sociologies of mechanical human behavior. No significant, non-trivial sociology of autonomous self-activity is possible, since there is no possibility of predicting genuinely free, autonomous activity. This means that while Marxism may attempt to investigate, analyze and interpret human activity under the institutions of modern slavery – using scientific, dialectical or any other semi-logical means – it can tell us very little of any detailed significance about what the abolition of capital and state might actually look like. And to the extent that Marxist ideologies demand any particular forms, stages or means of struggle they will always necessarily make the wrong demands. Because the only right forms, stages and means of struggle are those chosen by people in revolt constructing their own methods. Council communism, as a form of Marxism, is not essentially different from the other ideologies of social democracy on this score. Nor, for that matter, are all the various ideological variations of anarchism struggling for an increased share in the ever-shrinking leftist-militant market.

Vaneigem himself understands to a great degree what is at stake here. This is one major reason Vaneigem’s text still inspires anarchists around the world. And the reason we decided to serialize the original translation of his Treatise in Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed back in the ‘80s. As he explains in his introduction:

Vaneigem himself understands to a great degree what is at stake here. This is one major reason Vaneigem’s text still inspires anarchists around the world. And the reason we decided to serialize the original translation of his Treatise in Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed back in the ‘80s. As he explains in his introduction:

“ From now on the struggle between subjectivity and what degrades it will extend the scope of the old class struggle. It revitalizes it and makes it more bitter. The desire to live is a political decision. We do not want a world in which the guarantee that we will not die of starvation is bought by accepting the risk of dying of boredom.”

And, in the first chapter of his Treatise:

“The concept of class struggle constituted the first concrete, tactical marshaling of the shocks and injuries which men live individually; it was born in the whirlpool of suffering which the reduction of human relations to mechanisms of exploitation created everywhere in industrial societies. It issued from a will to transform the world and change life.”

[pullquote]Class struggle is not a metaphysical given. It is the cumulative result of actual flesh-and-blood personal decisions to fight enslavement or submit to it.[/pullquote]

Class struggle is not a metaphysical given. It is the cumulative result of actual flesh-and-blood personal decisions to fight enslavement or submit to it. Those who wish to reduce these personal decisions to effects of social laws, metaphyiscal principles, psychological drives or ideological dictates are all our enemies to the extent that we refuse to submit. And we do refuse.

1. La Société du Spectacle was first translated into English as The Society of the Spectacle by Fredy Perlman and Jon Supak (Black & Red, 1970; rev. ed. 1977), then by Donald Nicholson-Smith (Zone, 1994), and finally by Ken Knabb (Rebel Press, 2004).

2. Traité de savoir-vivre à l’usage des jeunes générations was first translated into English by Paul Sieveking and John Fullerton as The Revolution of Everyday Life (Practical Paradise Publications , 1979), then by Donald Nicholson-Smith (Rebel Press/Left Bank Books, 1994) and (Rebel Press, 2001).

3. Dogan, Mattei. “How Civil War Was Avoided in France.” International Political Science Review/Revue internationale de science politique, vol. 5, #3: 245–277.

4. In his 1955 essay, “Introduction to a critique of urban geography” (originally appearing in Les Lèvres Nues #6), Guy Debord suggests that: “Psychogeography could set for itself the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals. The adjective psychogeographical, retaining a rather pleasing vagueness, can thus be applied to the findings arrived at by this type of investigation, to their influence on human feelings, and even more generally to any situation or conduct that seems to reflect the same spirit of discovery.” (Ken Knabb, editor and translator, Situationist International Anthology, 1989, p. 5.)

5. Unitary urbanism consists in an experimental “critique of urbanism” that “merges objectively with the interests of a comprehensive subversion.” “It is the foundation for a civilization of leisure and play.” (unattributed, “Unitary Urbanism at the end of the 1950s,” Internationale Situationiste #3, December 1959.)

6. By the time the SI disbanded in 1972 Guy Debord and Gianfranco Sanguinetti (relatively new to the organization) were the only remaining members.

7. René Viénét is the listed author of Enragés and Situationists in the Occupation Movement: Paris, May, 1968, essentially the SI’s account of its activities during the May Days, written in collaboration with others in the group.

8. René Riesel was one of the Enragés at Nanterre who went on to join the SI.

9. Gianfranco Sanguinetti is notorious for his post-Situationist activities, most importantly, his scandalous authorship – under the pseudonym Censor – of The Real Report on the Last Chance to Save Capitalism in Italy, which was mailed to 520 of the most powerful industrialists, academics, politicians and journalists in Italy, purporting (as an assumed pillar of Italian industrialism) to support the practice of state security forces using terrorism under cover in order to discredit radical opposition. When Sanguinetti revealed his authorship he was expelled from Italy.

10.This episode led to a split in the Lettrists and the later founding of the more radical Lettrist International, which itself was one of the founding groups of the Situationist International. Debord was a member of the Lettrist International. Unfortunately, it’s reported that a quick-thinking organist drowned out most of the Notre-Dame intervention.

11. The full title is On the Poverty of Student Life considered in Its Economic, Political, Psychological, Sexual, and Especially Intellectual Aspects, with a Modest Proposal for Doing Away With It. Mustapha Khayati was the main, but not the sole, author.

12. “Pro-situationist” or “pro-situ” was the (sometimes derisive) label given by Situationists to those who (often uncritically, or less than fully critically) supported and promoted Situationist ideas and practices as they (often incompletely) understood them, rather than constructing their own autonomous theoretical and practical activities. This includes most of the Situationist-inspired activities in the SF Bay area in the 1970s wake of the SI’s own dissolution. There was a proliferation of tiny pro-situ groups like the Council for the Eruption of the Marvelous, Negation, Contradiction, 1044, the Bureau of Public Secrets, Point Blank!, The Re-invention of Everyday Life and For Ourselves. Most Situationist-influenced anarchists at the time (for example, Black & Red in Detroit, and a bit later John & Paula Zerzan’s Upshot, the Fifth Estate group, Bob Black’s Last International, the group around Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed, and others) stood apart from these interesting attempts to carry on the Situationist project in a very different North American social, political, economic and cultural situation, if for no other reason than basic disagreements with the SI’s Marxism, councilism, fetishization of technology, ideological rationalism, inadequate ecological critique and seemingly complete ignorance of indigenous resistance. (Which is not to say that Situationist-influenced anarchists didn’t have their own, often equally-debilitating problems.)

13. See Ken Knabb’s translator’s introduction to the third chapter of Raoul Vaneigem’s From Wildcat Strike to Total Self-Management, included in Knabb’s Bureau of Public Secrets web site at: http://www.bopsecrets.org/CF/selfmanagement.htm

14. “Vaneigemism is an extreme form of the modern anti-puritanism that has to pretend to enjoy what is supposed to be enjoyable…. Vaneigemist ideological egoism holds up as the radical essence of humanity that most alienated condition of humanity for which the bourgeoisie was reproached, which ‘left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest’….” – page 256 of Ken Knabb, “The Society of Situationism” published in Public Secrets (Bureau of Public Secrets, 1997).

15. Debord borrowed heavily from the Socialisme ou Barbarie group’s flirtation with council communism, or councilist social democracy. He was a member of S. ou B. for a time.

16. Vaneigem’s is so far the best update of Max Stirner’s original nineteenth century phenomenology of modern slavery and autonomous insurrection, Der Einzige und Sein Eigenthum, mistranslated into English as The Ego and Its Own. (A more accurate translation would be The Unique and Its Property.) Although Vaneigem mentions Stirner in his text, it is unclear how well he understands Stirner’s intent, and how much he has been influenced by Stirner.